The controversial history of sex and the Church. How it all began and how we got here

Those who want to worry only about their own problems perish over those of others; those who worry about the evils of the world, want to pass quietly, administering their medicines without hearing the protests of the sick.

It thus becomes a comical discussion which, while legitimate – the Church’s universal claim demands that her problems be of interest to all men – ends up being legitimised by those who condemn her. This usually takes the discussion to an absurd level. A number of prophets and biblical scholars demand the “modernisation” of the Church, which “adapts” to modern times and abandons “retrograde” positions.

The foundation, of course, is never to purify the Church, or to bring her more into line with the teachings of Christ. It is an opinion of conflict, of someone who judges modern values superior to the old ones, and therefore any person or institution of good must adopt them. For most of these apostles, the Church’s position is merely a symptom of an incomprehensible reactionaryism. The Church should take the world’s step as if the world were the foundation of her values.

The fundamental point of discussion is a second problem which is usually neglected. Discussions about the Church tend, incomprehensibly, to forget Christ. That is, in a discussion with a communist, it is not on anyone’s mind to demand that the party abandon the idea of class struggle. This is because the fundamental thing is understood: to ask the Party to abandon class struggle is to ask it to abandon communism. The discussion thus passes: one discusses the evils or virtues of communism, but not its essence.

The Church has no legitimacy to change her position because she believes that she does not belong to herself. The discussion must therefore begin with what models it, not with what it wants to model.

What happens to the Church is precisely the opposite. The contenders never demand that the Church abandon Christianity; yet they treat it as if the Church could choose it. This is the case in all matters: the Church must rethink her position on marriage, on abortion, on euthanasia, as if she were free to create her doctrine at every moment. The most important point for any discussion about the Church is thus to understand its foundations: the Church believes in the morality of Christ, and believes that this morality has been revealed by the Bible and the tradition of the Church herself.

It is thus possible to discuss the Church’s position on sex in any of its facets. It is spurious, however, to enter into the discussion with ideas of contemporaneity. The Church does not have the legitimacy to change her positions because she believes that she does not belong to herself. The discussion must therefore begin with what models it, not with what it wants to model. Does the Church have, in the Bible and in her tradition, a foundation for her norms on sex? Only this can be a discussion about the Church that really interests the Church.

It so happens that in sexual matters tradition extends far beyond the Church. Of course there are in the Bible examples of the spectacular death of Onan, who was struck down by the spilling of his semen on the ground, or of the always quoted Sodom, which gives its name to the sin into which he fell. There is also the phrase of Christ, who is probably the only one that tightens the law of the Jews: “Let not man put asunder that which God has joined together”, the order that founds the indissolubility of marriage, coming from the one who, in everything else, was held in a relaxed state.

The different episodes could ask for different discussions. However, the discussion about onanism, sodomy, or sex in marriage has the same idea behind it. And this idea, as we said, extends far beyond the Church. Interestingly, the sexual position of the Church owes as much to the Bible as to ancient philosophy. It is long before Christ that serious protests against what will be the basis of the Church’s position on sex are beginning to be heard: the disorder of passions. Both Stoics and Epicurists, both academics and Pythagoreans, perceive passions as the state in which man does not control himself. He who lets himself be dominated by gluttony, laziness, or physical attraction is the one who has no control over himself, who is not free. The virtue of continence thus begins to be praised as one of the great signs of strength and humanity.

It is proper for animals to follow their instincts, it is proper for the weak to succumb to their passions – so much so that, in Greek literature, the conqueror is always an effeminate figure, weak, incapable of dominating himself – and the virtues of continence, in any aspect, are countless. It may change the foundation, but it does not change the method. The epicurist seeks temperate pleasure and therefore repudiates excess, the stoic seeks to rid himself of passions and therefore also seeks temperance. The life of Mainland Man is the life of the one who can find himself under the bodily conditioning, of the multitude of uncontrolled passions that set Man against himself and dominate his will.

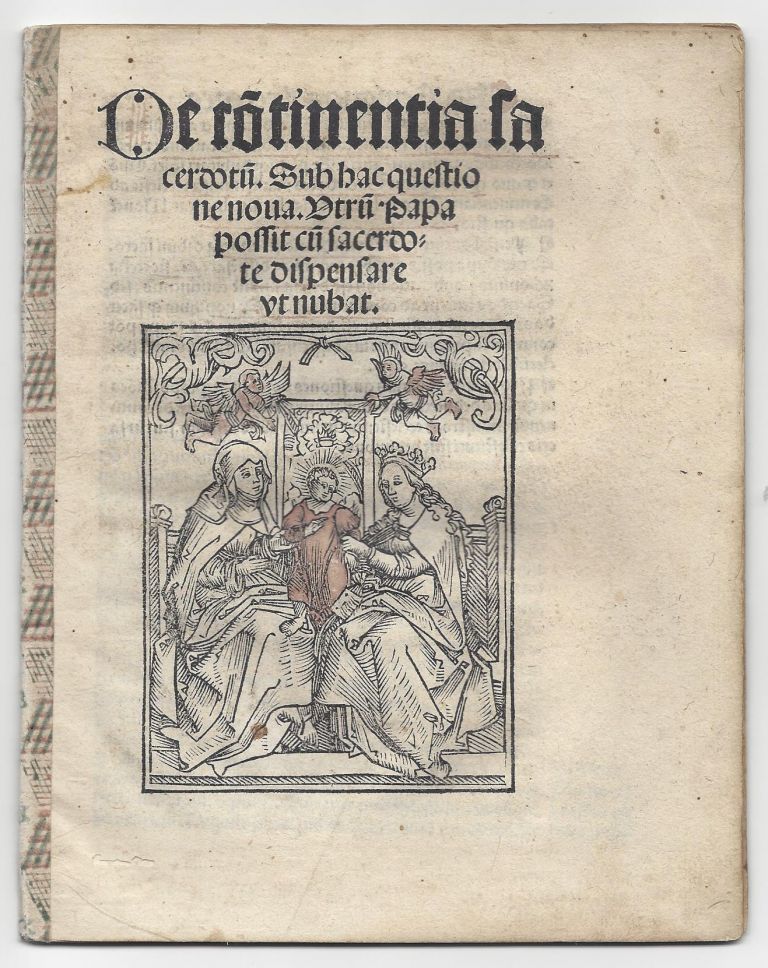

This type of philosophy has been widely grasped by the Church. This is also the way of thinking found in St Augustine’s De Continentia, or, without sexual mentions, in the type of life idealised by the Fathers of the Desert. Sexuality is lived according to a greater idea of renouncing all kinds of passions, which hide the true Man. Christ, who chose the pain of the Cross, who fasted for forty days in the desert, would be the greatest model of this type of life.

Continence, however, is not the only idea the Church has about sex. There is, in the path of Greek and Roman thought on the ordering of passions, a will to order the world in relation to Christ. Sex, the great creative power of man, must also be ordered. Not only restrained, but in order to something. From the beginning, Christianity has been taken as a life choice which can be applied to every moment of life. It is not only a matter of doing good deeds; ordinary actions can also be transformed into Christian actions. This is because, since Saint Paul, Christ is not only seen as the best of men; he is seen as the very foundation of goodness.

The transformation of the humiliating cross into a moment of glory clearly shows the Church’s transforming power. Christ’s greatest miracle lies precisely in his ability to transform into Good that which was not. The biblical examples are many. What does the good thief actually do? There is no action that redeems him, only the power of Christ. This leads the first Christians to believe that every action can be lived out in order for Christ. Not only the civic voluntarism of our day, but even the most banal, like eating or sleeping. Everything can be transformed into Good by the power of Christ. Sex, too, can be lived as a sacred thing, inserted in the ideal of Christian life.

What is most often unworthy of non-believers is the discrepancy between the ideal of life proclaimed by the Church and the rigidity of her doctrine. Theoretically, this “ideal of Christian life” has love as its basic premise. Yet there seems to be a cold indifference on the part of the Church to this same love in the most varied forms. The case of married couples, like the simple case of two boyfriends in Camillian passion, viewed with reservations by the Church, clashes with our usual understanding of love.

The idea of repressed sexual impulses, which would represent a true and more natural background of man, seems the reverse of Greek-Christian anthropological theory. Sex, transformed at the decisive moment of human identity, does not tolerate intrusions or restrictions and becomes seen as the most intimate and profound form of freedom.

This is because the Church’s understanding of love is completely different from that given to us by the senses. The difference between Eros, romantic love, and Agape, love as mentioned in St Paul’s letters, has already been widely dissected by philologists. The essence of the discussion, however, lies in the ecclesial idea of love as a commandment. That is, for the Church, destined to fulfil a very clear command – “Love one another” – love is a commandment. Now an order is given only in relation to something that can or cannot be obeyed. Love is perceived as a choice, not as something that happens.

There is, in Christian love, an ethical sense. One can love independently of passions, and even to the chagrin of them. Love, taken together with the idea of Christ being the foundation of the Good, is what makes it possible to perceive the indissolubility of marriage, or the apparent indifference to all kinds of passions. The Church knows that they exist, but it is not in relation to them that sex must be ordered. Human love is above all ethical and sacred, the sacrament is above passions and represents the true spirit of Christian love: a love that is above all ethical and free, free to the point of dismissing passions.

The real change in this state of mind was rather late. Of course, there are already some sentimental after-effects of romanticism which have moved society; however, the eighteenth-century bourgeoisie, helped also by a certain economic pragmatism, still perceives love as a choice and even as self-denial, albeit in intimate ways. The Freudian revolution, however, has dealt a powerful blow to the social understanding of the Church’s views. The idea of repressed sexual impulses, which would represent a true and more natural background for man, seems to be the reverse of Greek-Christian anthropological theory. Sex, transformed at the decisive moment of human identity, does not tolerate intrusions or restrictions and becomes seen as the most intimate and profound form of freedom.

The sacralization of sex thus makes it the main element of conflict between two opposing visions of the world. Sexuality becomes such a modern obsession that even the Church, hated by the contemporary world, has difficulty in dealing with the shattered parts of this world. David Lodge’s novel How far can one go?, about a group of Catholics interested in knowing, as the title itself indicates, how far one can go in premarital sex – and who clearly have not read St. Alphonsus Liguori, or would have detailed answers to the question – demonstrates the extent to which sex has become capital matter within the Church itself.

Beyond the specific points of doctrine and casuistry, the Church’s position on sex is based on these presuppositions. Love is ethical and active before passion and is defined by Christ, not by our feelings. Continence is not a punishment, but a virtue which enables man to overcome that which he does not control. Let the noise then numb the doctrine, let history be confused with philosophy, or let fear of the world lead to lukewarmness and dialectic flowerings, or let mercy and compassion protect the heads of the most aggressive beaks.